Contact and Additional Information to be addressed to: Katherine Aumer, PhD

kaumer@hpu.edu

1166 Fort Street Mall -- FS Building, Room 309

Honolulu, Hawai’i 96813

Research investigating the relationship between jealousy and relationship satisfaction has yielded conflicting results (Demirtas & Donmez, 2006). Additionally, few scholars have investigated the impact of compersion (positive feelings for a significant other when he or she is involved in a rival romantic relationship) on relationship satisfaction (Duma, 2009). We predicted that there would be a significant interaction between gender, jealousy/compersion, and relationship status on relationship satisfaction. We reasoned that one's relationship goal (e.g., to be exclusively monogamous) will greatly affect how jealousy and compersion impact relationship satisfaction. Of our 302 participants, relationship status significantly interacted with emotional jealousy and compersion, such that those in monogamous relationships were happier when they had higher degrees of emotional jealousy and compersion had no effect on relationship satisfaction. In contrast, compersion positively predicted relationship satisfaction for those in non-traditional relationships. An understanding of the goals for each individual in a relationship may be important in understanding what types of emotions will positively or negatively impact one’s relationship satisfaction.

Scholars have long been fascinated by the question as to whether or not jealousy is a cultural universal. They have asked: Are there gender differences in what sparks jealousy? How do people deal with jealousy? However, since the 1970s and 1980s, social commentators have begun to address another, very different, type of question: Can people alter their jealous reactions to their partners' affairs? What impact does jealousy (or the lack thereof) have on intimate relationships? Are multiple relationships really a threat to intimate relationships?

A plethora of scholars have addressed the first two sets of questions. Our major concern, however, will be the third set of questions. Specifically, we ask: Are there gender differences in the tendency to feel jealousy or "compersion" (i.e., to take pleasure in one's partner's sexual pleasure in other sexual encounters)? (Precisely what theorists mean by feelings of "compersion/empathy" will be discussed in a later section.) What is the impact of a tendency to be jealous or to take pleasure in a partner's pleasure (to have a compersion reaction) on relationship satisfaction? Does gender, one’s ability to be jealous or compersive, and type of relationship (monogamous versus non-traditional) interact in shaping relationship satisfaction?

A. Traditional Perspectives on Jealousy

According to the American Psychological Association (VandenBos, 2007), jealousy can be defined as:

“A negative emotion in which an individual resents a third party for appearing to take away (or likely to take away) the affections of a loved one” (p. 506).

Researchers in Israel (Nadler & Dotan, 1992) and the Netherlands (Bringle & Buunk, 1986) found that individuals experience the most jealousy and the most severe physiological reactions (e.g., trembling, increased pulse rate, nausea), when a loved one's affair poses a serious threat to their dating or marital relationship. Berscheid and Fei (1977) also provided evidence that low self-esteem and the fear of loss are important factors in fueling jealous passion. They found that the more insecure men and women are, the more dependent they are on their romantic partners and mates, and that the more seriously a relationship is threatened, the more fierce their jealousy.

B. Is Jealousy a Cultural Universal?

Most scholars assume that jealousy is a cultural universal—known to exist in all cultures—although culture and historical era shape how jealousy is defined, what sparks it, and how men and women deal with it. Anthropologists, cultural psychologists, historians, and social psychologists tend to focus on the influence of culture and historical era on people's perception as to the nature of jealousy (Hatfield, Rapson, & Martel, 2007). Evolutionary psychologists tend to focus on the universality of jealousy, arguing for its antecedents in human kinds' evolutionary and genetic heritage.

According to Buss (1994), for example, in the course of evolution, men and women were programmed to differ markedly in the kinds of things that incite jealousy. Since men can never know for sure whether the children they think are theirs (and in which they may choose to invest their all), are really their own, men should find sexual infidelity the most worrying. Women, on the other hand, who know that any children they conceive are theirs, should worry far less about their mates’ sexual liaisons. What worries women is the possibility that their mates may be forming a deep, emotional attachment to a rival, thus squandering scarce resources on another. Scientists have also collected evidence that in men, sexual infidelity incites the most jealousy, while in women, the discovery that their husbands have formed a deep emotional attachment to another women, and/or is squandering resources on her is most upsetting (Buss & Schmitt, 1993; Glass & Wright, 1992).

Cultural and evolutionary theorists have also collected considerable evidence indicating that men and women often respond differently to jealous provocation. For example, Israeli psychologists Nadler and Dotan (1992) found that when jealous men tend to concentrate on shoring up their sagging self-esteem, jealous women are more likely to try to do something to strengthen the relationship. Bryson (1977) speculated that these gender differences may well be due to the fact that most societies are patriarchal. In such societies, it is acceptable for men to initiate relationships. Thus, when men are threatened, they can easily go elsewhere. Women do not have the same freedom; therefore, they devote their energies to keeping the relationship from foundering.

Studies in a variety of countries—including Israel (Nadler & Dotan, 1992) and the Netherlands (Buunk, 1982)—have found that these same gender differences exist in many parts of the world. When Harris (2003) conducted a meta-analysis of more than 100 studies designed to determine whether there are gender differences in what sparks jealousy, she found little support for the evolutionary contention. Harris reviewed men’s and women’s self-reports and psychophysiological reactions, as well as data on morbid jealousy, spousal abuse, and jealousy-inspired homicides in a variety of jealousy provoking situations. In summarizing this voluminous research, she concluded that:

The results provide little support for the claim that men and women are innately wired to be differentially upset by emotional and sexual infidelity (p. 117).

Jankowiak (1995) concurs, arguing that in all cultures, both men and women find emotional and sexual infidelity extremely upsetting. He contends that it is male power, not innate gender differences, that accounts for differences in men's and women’s willingness to express their jealous feelings.

C. The Impact of Jealousy on Relationship Satisfaction

When theorists speculate about the possible relationship between jealousy and relationship satisfaction, they often make very divergent predictions. Jealousy can be seen as a "cute" correlate of young love, or evidence that the lover cares about his beloved — an emotion that binds a couple together and prevents a rival's mate from poaching. Jealousy can also be seen as a neurotic manifestation of insecurity ("she is insanely jealous") or a rational reaction to the discovery of a trusted mate's infidelity and betrayal ("Who wouldn't be jealous?). Unsurprisingly, although theorists have often investigated the links between jealousy and relationship satisfaction, the results of such correlational studies are often conflicting (Demirtas & Donmez, 2006). Some research indicates that jealousy is positively related to relationship satisfaction (Dugosh, 2000; Fleishmann, Spitzberg, Andersen, & Roesch, 2005). However, other research contends that the two are negatively related (Guerrero & Eloy, 1992; Hansen, 1982), and that participants may differ in what they assume is meant by "jealousy."

Pfeiffer and Wong (1989) have shown that there are multiple dimensions to jealousy, specifically: cognitive, behavioral, and emotional. Cognitive jealousy can be conceived as obsessions and suspicions about one’s partner’s fidelity. Behavioral jealousy is seen as acts that one does when suspecting infidelity, like checking messages on their partner’s phone or rifling through their partner’s clothes in attempts to find evidence of infidelity. Finally, emotional jealousy encompasses feelings of hurt or rejection one would feel should one’s partner be suspected of flirting, dating, or having relations with another person. Considering these dimensions of jealousy and the conflicting data on how jealousy impacts satisfaction in relationships, we contend that the correlation between jealousy and relationship satisfaction may be influenced by a host of intervening variables — for this paper, we are specifically focusing on the type of jealousy and the status of the relationship: mongamous vs. non-traditional.

D. Compersion and/or Empathy

In the 1970s and 1980s, at the height of the Sexual Revolution, social commentators began to suggest that a traditional, patriarchal, monogamous relationship should not be the social ideal. Theorists such as O'Neil and O'Neil (1984), in Open Marriage, for example, proposed that many couples might be happier and more satisfied if their marriages be supplemented by occasional extramarital activities, such as "wife swapping," "swinging," and the like. According to the folklore, such social experiments did not work out very well and were likely to lead to divorce and disease. However, there is little compelling evidence in praise or in criticism of such experiments and those that followed (see Conley, Ziegler, Moors, Matsick, & Valentine, 2013).

In recent years, however, a few social commentators have once again begun to propose that couples would do well to consider alternative types of romantic and sexual relationships. Talk shows, for example, often feature couples who testify to the advantages (or disadvantages) of new types of romantic and sexual relationships where partners are allowed to seek sexual satisfaction outside of their normal partner — among them casual sex, open relationships, and polyamorous relationships (open relationships are dyadic relationships in which partners are emotionally committed to one another, but are not sexually exclusive). Polyamorous relationships seek to achieve the same strong emotionally committed bonds, but with multiple partners. Polyamory is often considered to be "responsible non-monogamy" (Anapol, 1997, p. 19).

Polyamorous relationship structures are extremely diverse and can assume a variety of different forms depending on what the couples consider to be relevant relationship rules (Duma, 2009). For example, such relationships can consist of three or more people who may or may not all be involved with each other. Two different relationship structures for a polyamorous relationship, consisting of just three people, are a “V” and a “triangle”. Each point represents a person, and each line represents a connection. A “V” is a relationship in which one person (the apex of the “v”) has two partners, and the two partners each share the same person. A triangle, on the other hand, is a relationship in which all three participants are involved with each other. The V and the triangle are the simplest of polyamorous relationship structures.

When more people are involved, the relationship structures can get very complex. With emotional and sexual commitments being shared in these non-monogamous relationships, jealousy may (or may not) have a profound impact on relationship satisfaction. Theoretically, if people naturally experience (or can be taught to experience) a certain kind of empathy (i.e., compersion), then they may avoid many of the pitfalls found to be associated with alternative relationship structures.

Compersion is often described as the opposite of jealousy-—not just the absence of jealousy, but the experience of an opposite emotion (joy or happiness) when learning that a romantic partner is sexually involved with another lover. There is some support for the claim that jealousy and compersion are opposite emotions (Duma, 2009; Visser & McDonald, 2007). However, compersion has only been studied in relation to polyamorous relationships. Do feelings of compersion appear in monogamous relationships? Interestingly, Morrison, Beaulieu, Brockman, and O’Beaglaoich (2013) found that those in polyamorous relationships tend to have greater levels of intimacy than their monogamous peers, suggesting that if polyamorous couples truly experience more compersion than their monogamous peers, then these feelings may possibly contribute to heightened intimacy within the relationship.

Research on compersion is relatively nascent. When one thinks of compersion, one may think it is only necessary for people in relationships that will involve people outside of the couple. However, compersion is also an empathic feeling that emphasizes the welfare and happiness of the other partner. Such an emphasis on the other person’s happiness and welfare (to the point where it could damage one’s own potential welfare or maintenance of the couple) is similar to agape and evokes a sense of altruism. Past research has shown that agape is positively correlated with relationship satisfaction (Meeks, Hendrickson, & Hendrickson, 1998). Thus, it may be that compersion in general is good for all relationships. Some may speculate that compersion may be an emotion that can only be experienced by people in polyamorous relationships. However, many exclusive and non-exclusive monogamous couples may find that having happiness for their partner’s extradyadic relationships, necessitates the ability to understand and empathize with their partner's needs of intimacy. This ability to understand, empathize, and feel happy for their partner's exploration of intimate others, may actually bolster the intimacy and satisfaction within the dyad.

In the following study, we will focus on these two different emotions (compersion and jealousy) and their association with relationship satisfaction. We contend that the goals of the relationship, as in “being monogamous” or “being polyamorous,” will greatly impact the relationship between compersion, jealousy, and relationship satisfaction. Although compersion may be a worthwhile emotion in general, it may be counterproductive in relationships that are intended to be monogamous. The idea that those in reported monogamous relationships can have extradyadic relationships or components may seem new or even counterproductive to the goal of monogamy; however, extradyadic relationships have been reported and are not uncommon in monogamous relationships, especially in homosexual relationships (Leigh, 1989). Compersion may be especially important to cultivate in monogamous relationships that allow for the possibility of extradyadic relationships. However, individuals may find that the maintenance of their relationship as “monogamous” may be more important than their partner’s happiness in an extradyadic relationship. Thus, we suspect that a third variable of importance will be relationship style (i.e., whether the person in a relationship that he/she considers to be “single”, “monogamous”, “open”, or “polyamorous”.) In this study, we investigate the following two questions and hypotheses:

Question 1: Do men and women differ, on average, on their compersion scores?

Question 2: Do gender, feelings of compersion and jealousy, and type of relationship (single, monogamous, open, or polyamorous) interact in shaping relationship satisfaction?

Hypothesis 1: In concurrence with previous research, compersion and jealousy will have a strong negative correlation — lending support to the claim that compersion is the opposite of jealousy.

Hypothesis 2: Higher compersion scores will be associated with higher relationship satisfaction depending on the relationship style. Thus, those who are single, polyamorous, or open will be more satisfied with higher levels of compersion, but those in monogamous relationships will not be. Conversely, higher jealousy scores will be associated with lower relationship satisfaction across all relationship styles (single, monogamous, open, or polyamorous).

Participants

Participants consisted of students from HPU and friends and family who were recruited online through Facebook and from a local anonymous polyamorous group in Honolulu, HI. All potential participants were told that the survey was intended to better understand factors that could affect relationship satisfaction. Additionally, participants were told that their answers would be anonymous. The survey was constructed online using Qualtrics and the URL for the survey was posted online using the psychology department’s participation recruitment site at HPU, Facebook, and through email to an anonymous polyamorous group. Three hundred and eighty nine adults initiated the online survey. However, several participants did not complete the survey and the final sample size consisted of 302 (90 males and 202 females, and 10 who stated other) participants. Due to the lack of individuals who listed themselves as “other”, we eliminated their scores from any analysis focused on gender differences (their scores were included for all other analyses). Age ranged from 18 to 72, average age was 34.39 (SD = 12.42). Preliminary analysis of missing data indicated the pattern of missing data was missing at random (MAR); that is, missing values on predictors were generally unrelated to relationship satisfaction.

Participants were asked to indicate their sexual orientation. Eleven participants chose not to answer this question. Of those participants who did answer the question, the majority of participants self-identified as Heterosexual (52%) then Bisexual (28%), Other (14%), Homosexual (5%), and Asexual (1%). Among participants who identified themselves as “Other” for sexual orientation, 63% of these participants specified that they were Pansexual. The remaining participants 37%, who identified as “Other,” described themselves as being “heteroflexible/homoflexible: mostly attracted to one sex, but open to the other sex”. Participants were asked to indicate their relationship status; possible answers included: “single, not currently in a relationship” (n = 79, 67% Women, 30% Men, and 3% Other), “in a monogamous relationship” (n = 87, 72% Women, 20% Men, and 8% Other), “in an open relationship” (n = 49, 63% Women, 30% Men, and 7% Other), or “in a polyamorous relationship” (n = 87, 63% Women, 35% Men, and 2% Other). “Single” individuals were asked to think of their last most recent romantic relationship and answer their questions according to that relationship and partner. Participants who were single were included in this study as a way to assess hindsight of jealousy and compersion on relationship satisfaction.

Procedures

Participants consisted of students from HPU’s Introductory Psychology Course, members of Facebook, and members of an anonymous polyamorous group in Honolulu, Hawai’i who were contacted via email. All participants received an email or computerized message asking them to take a survey in order to better understand relationship satisfaction. The survey link was provided in this message. No compensation, other than class credit for Introductory Psychology students was provided. After clicking on the link, participants were taken to an Informed Consent Form. If participants checked a box saying they read the Informed Consent Form, then they were allowed to continue to the rest of the survey.

Measures

Participants were asked to complete basic demographic questions, like age, sex, and race. Additionally, when asked about their current relationship status, participants were asked: “Which of the following best describes your current relationship: Single (not currently in a relationship with anyone, but was in a monogamous romantic relationship within the past 6 months), Monogamous (currently in a relationship with one other person and this relationship is exclusive), Open relationship (currently in a primary relationship with one other person; however, we are both allowed or have seen other people intimately), and Polyamorous (currently in an intimate relationship with multiple people who are all considered to be as important or “primary”). After participants filled out this question, they were taken to one of three surveys. Each survey was tailored specifically to their relationship status. Each of the following measures were altered to apply correctly to the person and their relationship:

Compersion Questionnaire. To measure compersion, a modified version of the Compersion Trait Questionnaire (Duma, 2009); a 25 item scale was included in the survey. Questions were answered on a 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree) Likert scale. This scale included questions like: “I’d be comfortable with my partner falling in love with someone else.” The scale was reliable for each relationship status in our sample, with a Cronbach’s alpha of .94, 95% CIs [.93, .95].

The Multidimensional Jealousy Scale (Pfeiffer & Wong, 1989) is a 24 item scale measuring three different dimensions of jealousy: Cognitive jealousy, emotional jealousy, and behavioral jealousy. Each dimension or subscale is measured with 8 items. The original scale assumed heterosexuality, so questions had to be modified to be non-discriminate in regards to sexual preference. So phrases such as “someone of the opposite sex” were changed to “someone else”. The Cognitive items measured frequency of thoughts such as: “I suspect that my partner is secretly seeing someone else”. These items were answered on a seven-point Likert scale, ranging from “never” to “all of the time”. Emotional items measured one’s emotional reaction to situations such as: “Your partner hugs and kisses someone else”. The items were answered on a seven-point Likert scale, ranging from “very pleased” to “very upset”. The behavioral items measured the frequency of jealous behaviors such as: “I look through my partner’s drawers, handbag, or pockets”. The items were answered on a seven-point Likert scale, ranging from “never” to “all of the time”. Each dimension of jealousy had good or excellent scale score reliability (i.e., as measured by Cronbach’s alpha): cognitive jealousy = .92, emotional jealousy = .91 and behavioral jealousy = .78, 95% CIs [.81, .91], [.87, .93], [.69, .85], respectively.

Relationship Assessment Scale (Hendrick, Dicke, & Hendrick, 1998) is a 7-item scale measuring relationship satisfaction in intimate relationships. The scale contains questions such as “How well does your partner meet your needs?” Items were answered on a five-point Likert scale, ranging from “not at all” to “very much”. For those in open and polyamorous relationships, the wording was changed to “partner(s)” instead of “partner”. Items were averaged across all participants. The scale had good reliability with Cronbach’s alpha = .84, 95% CIs [.81, .87].

All of these measures were modified depending on the relationship status of the participant. Qualtrics uses a logic routine that allowed us to designate a tailored survey for Single, Monogamous, and Polyamorous participants. Single participants received items modified to address their past, but most recent relationship; monogamous participants received the items as is, and open/polyamorous participants responded to the items for up to three of their most invested relationships.

In answering our first question, “Do men and women differ, on average, on scores of jealousy and compersion,” an independent samples t-test revealed a strong effect for gender. Women (M=2.00, SD=.93) scored higher on behavioral jealousy than men (M=1.72, SD=.74), t(260) = -2.30, p=.02, d=0.33). Women (M=3.53, SD=1.80) also scored higher on emotional jealousy than men (M=2.90, SD=1.64), t(291)= -2.77, p=.006, d=0.37. And although women (M=1.93, SD=1.39) scored higher than men (M=1.77, SD=0.92) on cognitive jealousy, this difference was not significant, t(291)= -0.94, p=.35, d=0.14. Men (M=5.30, SD=1.34) scored significantly higher on compersion than women (M=4.53, SD=1.54), t(248)=3.74, p<.001, d=0.53, see Table 1. Considering this gender difference, subsequent analyses will separate women’s and men’s scores for jealousy and compersion.

The first hypothesis stated that compersion and all dimensions of jealousy would be negatively correlated. The data supported this hypothesis. For men, compersion was strongly negatively correlated with emotional jealousy (r (72) = -.79, p < .001), but not correlated with cognitive (r (72) = -.15, p =.22) or behavioral jealousy (r (72) = -.11, p = .37). For women, compersion was negatively correlated with all dimensions of jealousy: cognitive (r (178) = -.18, p = .02), behavioral (r (178) = -.29, p < .001), and emotional (r (178) = -.80, p < .001). Thus, for both women and men, emotional jealousy seems to be the most strongly negatively correlated with compersion. Considering that emotional jealousy and compersion were so strongly negatively correlated (and for the women, all dimensions of jealousy were negatively correlated with compersion), we ran collinearity statistics by conducting a multiple regression with compersion as our dependent variable and all dimensions of jealousy as our independent variables. Tolerance was assessed and all levels of tolerance were above .80 for both women and men, and the variance inflation factor (VIF) was below 2 for both women and men, thus multicollinearity was not detected. Thus, in subsequent analyses, compersion will be used as a separate factor from the dimensions of jealousy.

To answer our second hypothesis: relationship satisfaction would depend on both the relationship status (i.e., single, monogamous, open or polyamorous) and compersion score, we tested the interaction between relationship status and compersion scores. Because interpreting an interaction between a categorical variable with 4 levels (i.e., relationship status) and a continuous variable (i.e., compersion and jealousy) can be difficult, we recentered the continuous variables around their respective averages, creating three distinct groups: average (within +1/-1 standard deviations of the average compersion score), 1 standard deviation above the average compersion score (high compersion), and 1 standard deviation below the average compersion score (low compersion). With the recentered score, we were able to conduct a 4x3 ANOVA using relationship satisfaction as the dependent variable and compersion and relationship status as our factors. This same process was carried out to answer the second part of our hypothesis: higher jealousy scores would be associated with lower relationship satisfaction. For each of the jealousies: cognitive, behavioral, and emotional jealousy, the scores were recentered creating 3 separate groups: average (within +1/-1 standard deviations of the average jealousy score), 1 standard deviation above the average compersion score (high jealousy), and 1 standard deviation below the average compersion score (low jealousy). Separate analyses were run for men and women due to finding statistically significant differences in jealousy and compersion (see above results). This type of analysis created very small subsamples for the men, with some analyses only including 3-5 men in the low or high groups for each type of jealousy or compersion. Thus, the following analyses, especially for the male sample, should be interpreted with caution.

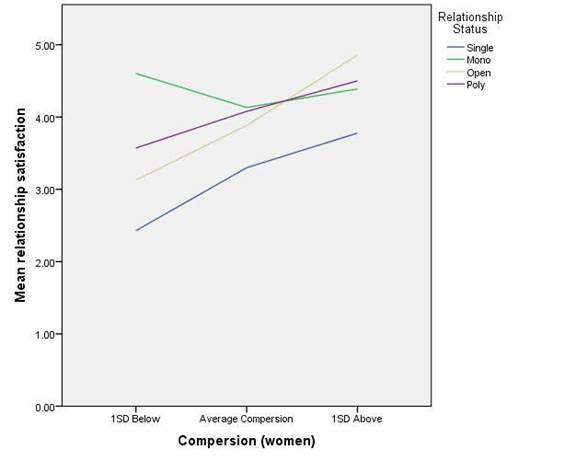

Women

Compersion. Using a 4x3 ANOVA with relationship style and compersion as the factors, and relationship satisfaction as the dependent variable revealed statistically significant main effects for relationship status, F(3,169)= 17.29, p<.001, partial eta2=.25, and compersion, F(2,169)= 9.32, p<.001, partial eta2=.11, in predicting relationship satisfaction. Supporting our second hypothesis, the interaction of relationship status and compersion, F(6,169)= 2.96, p<.01, partial eta2=.10, was statistically significant. A simple main effects analysis using a Bonferonni adjustment revealed that, for women, relationship satisfaction was dependent on compersion only when Single or in an Open relationship. See Figure 1 for an illustration of the differences. Women who were Single and scored low on compersion were less satisfied (M=2.43, SD=0.57) in their relationships than Single women who scored either average (M=3.30, SD=0.90) or high (M=3.78, SD=1.13) on compersion. Similarly, women in Open relationships who scored low on compersion were less satisfied (M=3.13, SD=0.86) than women in Open relationships who scored high (M=4.86, SD=0.57) on compersion. Surprisingly, relationship satisfaction for women in Monogamous and Polyamorous relationships were not dependent on their compersion scores. When scoring low on compersion, Monogamous women were significantly happier in their relationships (M=4.60, SE=0.24) than women who were Single (M=2.43, SE=0.27) or in Open relationships (M=3.13, SE=0.32). Overall, Single women were less happy in their relationships than any of the other relationship types if they scored low or average on compersion. When compersion was high, all women in all relationship types scored high on relationship satisfaction and there were no statistically significant differences between groups.

Cognitive Jealousy. Using a 4x3 ANOVA with relationship style and cognitive jealousy as the factors, and relationship satisfaction as the dependent variable revealed a statistically significant main effect for relationship status, F(3,178)= 18.81, p<.001, partial eta2=.25, and cognitive jealousy, F(2,178)= 17.75, p<.001, partial eta2=.18, in predicting relationship satisfaction. The interaction between relationship status and cognitive jealousy was not significant, thus post-hoc analyses of the main effects were conducted with a Bonferonni adjustment. Post-hoc analyses of relationship status revealed that Single women were significantly less satisfied (M=3.04, SE=0.11) in their relationships than women in monogamous (M=4.16, SE=0.11), open (M=3.81, SE=0.21), and polyamorous (M=4.00, SE=0.16) relationships. There were no statistically significant differences between the other three relationship statuses. Post-hoc analyses of cognitive jealousy revealed that women who scored high on cognitive jealousy were less satisfied (M=3.08, SE=0.43) in their relationships than women who scored average (M=3.94, SE=0.07) or low (M=4.24, SE=0.14) on cognitive jealousy. All other pair-wise comparisons were not statistically significantly different.

Behavioral Jealousy. Using a 4x3 ANOVA with relationship style and behavioral jealousy as the factors, and relationship satisfaction as the dependent variable revealed a statistically significant main effect for relationship status, F(3,178)= 18.83, p<.001, partial eta2=.25. The main effect for behavioral jealousy and the interaction of relationship status and behavioral jealousy were not statistically significant. Post-hoc analyses using a Bonferonni adjustment of relationship status revealed that Single women were significantly less satisfied (M=3.04, SE=0.11) in their relationships than women in monogamous (M=4.16, SE=0.11), open (M=3.81, SE=0.21), and Polyamorous (M=4.00, SE=0.16) relationships. There were no statistically significant differences between the other three relationship statuses.

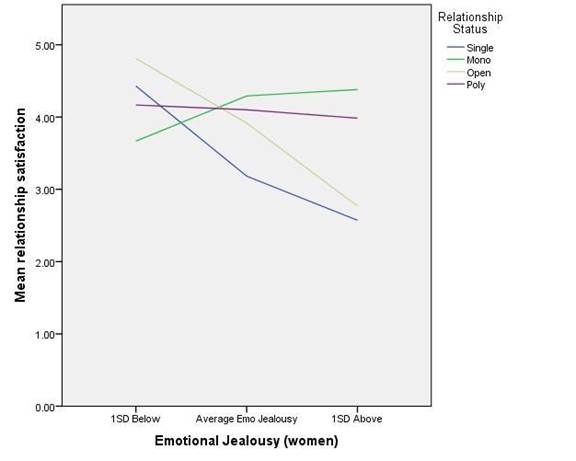

Emotional Jealousy. Using a 4x3 ANOVA with relationship style and emotional jealousy as the factors, and relationship satisfaction as the dependent variable revealed statistically significant main effects for relationship status, F(3,178)= 3.64, p=.01, partial eta2=.06, and for emotional jealousy, F(2,178)= 5.89, p<.01, partial eta2=.06, in predicting relationship satisfaction. Supporting our second hypothesis, the interaction of relationship status and emotional jealousy was statistically significant, F(6,178)= 4.96, p<.001, partial eta2=.14. A simple main effects analysis using a Bonferonni adjustment revealed that, for women, relationship satisfaction was dependent on emotional jealousy when Single or in an Open relationship. Women who were Single and scored high on emotional jealousy were less satisfied (M=2.57, SD=1.05) in their relationships than Single women who scored either average (M=3.18, SD=0.96) or low (M=4.43, SD=0.52) on emotional jealousy. Similarly, women in Open relationships who scored high on emotional jealousy were less satisfied (M=2.77, SD=0.34) than women in Open relationships who scored average (M=3.92, SD=0.51) or low (M=4.81, SD=0.18) on emotional jealousy. Surprisingly, relationship satisfaction for women in Monogamous and Polyamorous relationships were not dependent on their emotional jealousy scores. Interestingly, women in Monogamous relationships who scored high on emotional jealousy, were significantly happier in their relationships (M=4.38, SE=0.21) than women who were Single (M=2.57, SE=0.37) or in Open relationships (M=2.77, SE=0.37), see Figure 2 for an illustration.

Men

Compersion. Using a 4x3 ANOVA with relationship style and compersion as the factors, and relationship satisfaction as the dependent variable revealed a statistically significant main effect for relationship status, F(3,69)= 5.59, p=.002, partial eta2=.25. There was no statistically significant effect of compersion or interaction between relationship status and compersion. A post-hoc analysis using a Bonferonni adjustment revealed that, men who were Single and reporting about a past relationship, reported being less satisfied (M=3.28, SE=0.22), in their relationship than men in Open (M=4.22, SE=0.16), and Polyamorous (M=4.33, SE=0.15) relationships. Single and Monogamous (M=3.98, SE=0.18) men did not significantly differ in their satisfaction scores.

Cognitive Jealousy. Using a 4x3 ANOVA with relationship style and cognitive jealousy as the factors, and relationship satisfaction as the dependent variable revealed, again, a statistically significant main effect for relationship status, F(3, 68)= 5.23, p=.003, partial eta2=.22. There was no statistically significant effect of cognitive jealousy or interaction between relationship status and cognitive jealousy. A post-hoc analysis using a Bonferonni adjustment revealed that, men who were Single and reporting about a past relationship, reported being less satisfied (M=3.29, SE=0.19), in their relationship than men in Monogamous (M=4.08, SE=0.17), Open (M=4.09, SE=0.17), and Polyamorous (M=4.21, SE=0.15) relationships.

Behavioral Jealousy. Using a 4x3 ANOVA with relationship style and behavioral jealousy as the factors, and relationship satisfaction as the dependent variable revealed a statistically significant main effect for relationship status, F(3,68)= 8.73, p<.001, partial eta2=.32 and a main effect for behavioral jealousy, F(2,68)= 3.99, p=.02, partial eta2=.12. The interaction of relationship status and behavioral jealousy was not statistically significant. Post-hoc analyses using a Bonferonni adjustment of relationship status revealed, again, that Single men were significantly less satisfied (M=3.28, SE=0.17) in their relationships than men in Monogamous (M=4.18, SE=0.14), Open (M=4.12, SE=0.15), and Polyamorous (M=4.36, SE=0.14) relationships. There were no statistically significant differences between the other three relationship statuses. Post-hoc analyses using a Bonferonni adjustment of behavioral jealousy, revealed that men who scored Low on behavioral jealousy were significantly more satisfied (M=4.31, SE=0.15) in their relationships than men who scored Average (M=3.82, SE=0.09) on behavioral jealousy. The difference in satisfaction scores between men who scored Low on behavioral jealousy and High on behavioral jealousy (M=3.83, SE=0.14) approached significance (p=.07).

Emotional Jealousy. Using a 4x3 ANOVA with relationship style and emotional jealousy as the factors, and relationship satisfaction as the dependent variable revealed, again, a statistically significant main effect for relationship status, F(3,68)= 8.23, p<.001, partial eta2=.30. There was no statistically significant main effect for emotional jealousy or interaction between relationship status and emotional jealousy. A post-hoc analysis using a Bonferonni adjustment revealed that, men who were Single and reporting about a past relationship, reported being less satisfied (M=3.29, SE=0.16), in their relationship than men in Monogamous (M=3.98, SE=0.16), Open (M=4.19, SE=0.16), and Polyamorous (M=4.33, SE=0.15) relationships.

In answering our first research question: Do men and women differ, on average, on their scores of jealousy and compersion measures? We found that women scored significantly higher on both measures of behavioral and emotional jealousy and significantly lower on compersion than men. There was no gender difference with cognitive jealousy. These findings lend support to the idea that women may be more inclined (either through evolutionary or social-cultural reasons) to be vigilant about their partner’s potential infidelities or extradyadic relationships. In concurrence with previous research (Duma, 2009; Visser & McDonald, 2007), this study showed that the emotions of jealousy (specifically emotional jealousy) and compersion are strongly negatively correlated, supporting our first hypothesis. However, the variance inflation factor was well above multicollinearity limits of .20, suggesting that although the two factors are negatively related, they are not the “same” factor or opposites. More discussion of the relationship between compersion and emotional jealousy will follow.

Compersion

Results showed support for the first part of our second hypothesis: relationship satisfaction would depend on both compersion scores and the type of relationship. However, this was only true for women. Interestingly, compersion seemed to have had the greatest impact on women who were Single and in Open relationships. For these women, having more compersion was related to more satisfaction in their past or current relationships. Incidentally, although a similar trend was found for Polyamorous women, it was not significant and compersion scores seemed completely unrelated to Monogamous women’s satisfaction (see Figure 1). For men, compersion had no relationship with their relationship satisfaction. This is interesting, because compersion is often discussed in the literature (for a review see Duma, 2009) as an emotion that is important to polyamorous relationships, yet, it was the women in open relationships who seemed to benefit most from nurturing a sense of compersion. Although some literature categorizes open relationships as a form of polyamory (e.g., see Labriola, 1999), open relationships can encompass relationships that people in those relationships may not consider orthodox polyamory (e.g., swingers, “monogamish”, etc.). Similarly, some open relationships may allow for extradyadic relationships, but unlike polyamorous relationships, there may be an emphasis that these extradyadic relationships are temporary. Thus, it may be that for women in open relationships, compersion, or the ability to foster a loving compassion for a partner having extradyadic sexual relations, is especially important, because the activity may be temporary. However, for both men and women in polyamorous relationships, these extradyadic activities are seen as part of a lifestyle or for some; an orientation that will last for the lifetime of the relationship and thus neither jealousy nor compersion may be a contributing factor to their satisfaction.

Jealousy

When examining cognitive, behavioral, and emotional jealousy and their impacts on relationship satisfaction for both men and women, relationship style showed a consistent influence on relationship satisfaction, specifically, Single men and women were less satisfied than all other men and women in the three other relationship styles. Given that these Single individuals were reporting about a previous monogamous relationship that had terminated, it is not surprising to see less satisfaction reported. Men’s satisfaction scores were unrelated to emotional jealousy. What is surprising, or at least interesting, is to see that compersion and emotional jealousy had a different relationship to Single women’s satisfaction than it did for Monogamous women, suggesting that what seems to make relationships work in Monogamy is greatly dependent on perspective. While in the relationship, the satisfaction for monogamous women seemed to be higher if the compersion was low and the emotional jealousy was high. However, after the relationship had ended, it seemed that retrospectively, the heightened emotional jealousy and low compersion actually contributed to less satisfaction. This finding suggests that for Monogamous women still in the relationship, emotional jealousy seems to be related to higher satisfaction in the relationship in contrast to Single women who were once in a monogamous relationship. Nadler and Dotan (1992) had found that jealous women were more likely to try to do something to strengthen the relationship, in comparison to jealous men. It may be that, for women currently in a Monogamous relationship, emotional jealousy and lack of compersion are seen as a healthy attempt at making the relationship work. While, after the relationship has dissolved, emotional jealousy and lack of compersion, in retrospect, may be seen as a futile attempt at making a relationship work. Suggesting, that emotional jealousy and compersion are related and have some influence on relationship satisfaction, but this relationship is dependent on one’s perspective; during the monogamous relationship, the emotional jealousy and lack of compersion may be seen as a sign of faith and desire to maintain exclusive bonds, while after the relationship has ended, it is now seen as a waste of time and a detriment to the relationship.

These findings show support for research that has found disparities in the relationship between jealousy and relationship satisfaction. Although some research has found a positive correlation (Dugosh, 2000; Fleishmann, Spitzberg, Andersen, & Roesch, 2005), other research has found a negative correlation (Guerrero & Eloy, 1992; Hansen, 1982). Our research suggests that aspects of both research is correct, in that for women who are successfully in a monogamous relationship, social pressures may require emotional jealousy and a lack of compersion as a way of increasing satisfaction. But for women whose monogamous relationships have failed, it may now seem obvious that the use of emotional jealousy and lack of compersion were detrimental.

Other than emotional jealousy, cognitive jealousy for women and behavioral jealousy in men across all the relationship styles was related to less satisfaction in the relationship(s). Cognitive jealousy concerns suspicions and thoughts about a potential partner’s infidelity. Although it may seem impossible that a partner could cheat on someone while in an Open or Polyamorous relationship, this is not true. Both relationship types depend strongly on the rules and boundaries set forth by the people in those relationships. Additionally, although it may be acceptable and encouraged to sleep with or have relations with someone outside of the relationship, this may not be ok and raise suspicions in an Open and/or Polyamorous relationship if the partner did not communicate or clear the relation with the primary partner first. Thus, cognitive jealousy may be an obvious symptom of a lack of communication and trust in any relationship, which was related to lower satisfaction for women, but not men. For men, a higher level of behavioral jealousy was related to less satisfaction. Thus, for women, the vigilance and obsessions of possible infidelity, across all relationship types contributes to less satisfaction. While for men, the checking of his/her belongings (e.g., phone, emails, laundry, etc.) contributes to less satisfaction.

The complexity of people's relationships, classifications of relationship styles, and sometimes "taboo" nature of non-traditional relationships brought about many challenges in the research. Most of the measures used in the study were designed specifically for monogamous relationships, making it difficult to apply them to open and polyamorous relationships. In addition, polyamorous relationships themselves are so diverse, that it is difficult for any single scale to be widely applicable to all of them. Structures, rules, and hierarchies in polyamorous relationships are all extremely variable, making some questions valid for some relationships, and invalid for others. Although we felt like we addressed this issue by tuning the questionnaires appropriately for each type of relationship, we understand that this approach has not been validated by other researchers.

Similarly, it was difficult to accurately define terms in regards to relationship style. The line between open and polyamorous relationships can be blurry, and definitions may cross over. Polyamorous relationships can also be either open or closed depending on the conditions agreed upon by the partners. This was not taken into account in this study, which may have led to some difficulty for participants filling out the survey. Similarly, this study was advertised specifically to people who were in relationships. It is possible, however, that some participants who have never been in a relationship may have made up a relationship and taken the survey. Unfortunately, like most anonymous surveys, we have no way of measuring the validity of their romantic relationships. Additionally, our study did not measure relationship length. It could be that the length of the relationship may have a significant effect on jealousy and compersion. Being in relationship for a long period of time may open up more possibilities for experiencing jealousy and/or compersion. Also, this study relied on participants’ conceptions of monogamy, open and polyamory as these relationship terms were not predefined for them.

Thus, it is conceivable, that participants who were in monogamous relationships, but allowed for extradyadic relationships, were grouped with those in monogamous relationships that did not allow for extradyadic relationships. Additionally, we did not measure whether or not participants had extradyadic relationships (allowed or not) while in the romantic relationship. Such a difference may contribute to relationship satisfaction.

Another limitation was the demographics section of the survey. "Non-traditional relationships" are by their very nature uncommon. In retrospect, we realize that we might have profitably included a few additional demographic questions. Factors like gender identity were not taken into account, and we provided limited options for people to indicate their sexual preferences. There was, for example, a high representation of those who identified as gender fluid, gender neutral, pansexual, etc., and these options were not provided in the demographic section. Future researchers on sexuality would be well-advised to include such questions.

Finally, this research confirms that compersion and jealousy—specifically emotional jealousy are negatively correlated. The analyses performed in this study cannot deduce if these emotions are opposites. Although their influence on relationship satisfaction did correspond with the idea that the emotions could be opposites, the tolerance analysis did not find multicollinearity and thus suggests that these are still separate components—albeit highly negatively correlated. Thus, it may be that emotional jealousy and compersion lie on opposite ends of a spectrum or are separate components that are very negatively correlated. Duma (2009) wrote an overview of how compersion and jealousy may or may not be opposites. This analysis and argument are outside of the scope of this research. However, future research should still include compersion and jealousy as separate measures as this is, currently, an unanswered empirical question.

This study demonstrates that compersion and the different types of jealousies can contribute to relationship satisfaction differently, depending on relationships style and gender. Across all relationships styles, women seemed the least satisfied if high on cognitive jealousy. If monogamous or polyamorous, women’s compersion and emotional jealousy scores did not relate to their satisfaction scores. However, monogamous women were the most satisfied compared to their open and single peers, if they scored high on emotional jealousy. Compersion had the most impact on women if they were in Open relationships or Single. This is not demonstrated in the current literature, which suggests that compersion is primarily an emotion embraced by the polyamorous community (e.g., Duma, 2009). It may be that compersion is especially important for women in open relationships, as open relationships may test one’s ability to be in more complex polyamorous relationships. Additionally, women who are now single may see compersion as an important aspect of their future monogamous relationships. Future research should consider compersion to be important in other relationship styles outside of polyamory.

For men, across all relationship styles, being high on behavioral jealousy seemed to relate to less satisfaction. Compersion, cognitive jealousy, and emotional jealousy did not seem to influence satisfaction scores. Given the small subsamples in our male sample, it is important that these analyses be interpreted with some reservation. A replication of these findings would bolster the conclusions made by these initial findings. For both men and women, being single was related to less satisfaction.

Anapol, D. (1997). Polyamory: The new love without limits. San Rafael, CA: IntiNet Resource Center.

Berscheid, E., & Fei, J. (1977). Romantic love and sexual jealousy. In G. Clanton L.G. Smith (Eds.), Jealousy, (pp. 101-109). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall

Bringle, R. G., & Buunk, B. (1986). Examining the causes and consequences of jealousy: Some recent findings and issues. In R. Gilmour & S.W. Duck (Eds.), The Emerging Field of Personal Relationships, (pp. 225-240). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Bryson, J. B. (1977). Situational determinants of the expression of jealousy. In Annual meeting of the American Psychological Association, San Francisco.

Buss, D. M., & Schmitt, D. P. (1993). Sexual strategies theory: an evolutionary perspective on human mating. Psychological Review, 100(2), 204.

Buss, D. M. (1994). The strategies of human mating. American Scientist, 82: 238-249.

Buunk, B., & Hupka, R. B. (1987). Cross-cultural differences in the elicitation of sexual jealousy. Journal of Sex Research, 23(1), 12-22.

Buunk, B. (1982). Anticipated Sexual Jealousy Its Relationship to Self-Esteem, Dependency, and Reciprocity. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 8(2), 310-316.

Conley, T., Ziegler, A., Moors, A. C., Matsick, J. L. & Valentine, B. (2013). A critical examination of popular assumptions about the benefits and outcomes of monogamous relationships. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 17(2), 124-141.

Daly, M., & Wilson, M. (1988). Homicide. New York: Aldine de Gruyter.

Demirtas, A., & Donmez, A. (2006). Jealousy in close relationships: Personal, relational and situational variables. Turkish Journal of Psychiatry, 17(3), 181-191.

Dugosh, J. W. (2000). On predicting relationship satisfaction from jealousy: The moderating effects of love. Current Research in Social Psychology, 5(17), 254-263.

Duma, U. (2009). Jealousy and compersion in close relationships: Coping styles by relationship types. Mainz, Germany: GRIN Verlag.

Fleishmann, A. A., Spitzberg, B. H., Andersen, P. A., & Roesch, S. C. (2005). Tickling the monster: Jealousy induction in relationships. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 22(1), 49-73.

Glass, S. P., & Wright, T. L. (1992). Justifications for extramarital relationships: The association between attitudes, behaviors, and gender. Journal of Sex Research, 29(3), 361-387.

Guerrero, L. K. & Eloy, S. V. (1992). Relational satisfaction and jealousy across marital types. Communication Reports, 5(1), 23-31

Hansen, G. L. (1982). Reactions to hypothetical jealousy producing events. Family Relations, 31(4), 513-518.

Harris, C. R. (2003). A review of sex differences in sexual jealousy, including self-report data, psychophysiological responses, interpersonal violence, and morbid jealousy. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 7(2), 102-128.

Hatfield, E., Rapson, R. L., & Martel, L. D. (2007). Passionate love and sexual desire. In S. Kitayama & D. Cohen (Eds.), Handbook of cultural psychology (pp. 760-779).New York:Guilford Press.

Hendrick, S. S., Dicke, A., & Hendrick, C. (1998). The Relationship Assessment Scale. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 15(1), 137-142.

Hupka, R. B. (1981). Cultural determinants of jealousy. Alternative Lifestyles, 4(3), 310-356.

Hupka, R. B., & Ryan, J. M. (1990). The cultural contribution to jealousy: Cross-cultural aggression in sexual jealousy situations. Behavior Science Research, 24, 51-71.

Jankowiak, W. (Ed.). (1995). Romantic passion: A universal experience?. New York: Columbia University Press.

Labriola, K. (1999). Models of open relationships. Journal of lesbian studies, 3(1-2), 217-225.

Leigh, R. C. (1989). Reasons for having and avoiding sex: Gender, sexual orientation and relationship to sexual behavior. The Journal of Sex Research, 26 (2), 199–200.

Mead, M. (1931). Jealousy: Primitive and civilized. In S. D. Schmalhausen & V. F. Calverton (Eds.), Women’s coming of age: A symposium (pp. 35-48). New York: Liveright.

Meeks, B. S., Hendrick, S. S., & Hendrick, C. (1998). Communication, love and relationship satisfaction. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 15(6), 755-773.

Morrison, T. G., Beaulieu, D., Brockman, M., & Beaglaoich, C. Ó. (2013). A comparison of polyamorous and monoamorous persons: are there differences in indices of relationship well-being and sociosexuality?. Psychology & Sexuality, 4(1), 75-91.

Nadler, A., & Dotan, I. (1992). Commitment and rival attractiveness: Their effects on male and female reactions to jealousy-arousing situations. Sex Roles, 26(7-8), 293-310.

O'Neil, N. O. & O'Neil, G. (1984). Open Marriage: A new life style for couples. New York: M. Evans.

Pfeiffer, S. M., & Wong, P. T. (1989). Multidimensional Jealousy. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 6(2), 181-196.

Pitt-Rivers, A. H. L. F. (1906). The evolution of culture: and other essays. Clarendon Press.

Salovey, P., & Rodin, J. (1988). Coping with envy and jealousy. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 7(1), 15-33.

Tooby, J. & Cosmides, L. (1992). The evolutionary and psychological foundations of the social sciences. In J. H. Barkow, L. Cosmides, & Tooby (Eds.). The adapted mind: Evolutionary psychology and the generation of culture (pp. 19-136.). New York: Oxford University Press.

VandenBos, G. R. (Ed.: 2007). APA dictionary of psychology. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Visser, R., & McDonald, D. (2007). Swings and roundabouts: Management of jealousy in heterosexual ‘swinging’ couples. British Journal of Social Psychology, 46(2), 459-476.

White, G. L., & Mullen, P. E. (1989). Jealousy: Theory, research, and clinical strategies. New York: Guilford Press.

Wilson, M. I., & Daly, M. (1992). Who kills whom in spouse killings? On the exceptional sex ratio of spousal homicides in the United States. Criminology, 30(2), 189-216.

Table 1: Means and standard deviations for gender differences in jealousy and compersion

|

Compersion |

Cognitive Jealousy |

Behavioral Jealousy |

Emotional Jealousy |

Men |

5.3 (1.3) |

1.8 (0.9) |

1.7 (0.7) |

2.9 (1.6) |

Women |

4.5 (1.5) |

1.9 (1.4) |

2.0 (0.9) |

3.5 (1.8) |

Total |

4.8 (1.5) |

1.9 (1.9) |

1.9 (0.9) |

3.3 (1.8) |

Figure 1. Average relationship satisfaction by relationship type and compersion scores.

Figure 2. Average relationship satisfaction by relationship type and emotional jealousy scores.