Correspondence Email: tdune@une.edu.au

Human sexuality is constructed via public, interactional and private sexual scripts (Simon & Gagnon, 1986, 1987, 2003). However, normative sexual scripts often exclude or asexualize people with cerebral palsy. Consequently, rehabilitation counselling may rely on conceptual models of sexuality which are derived from typical populations. This paper presents a conceptual model of sexuality with disability relevant to rehabilitation counselling which reflects how people with moderate to severe disability construct their sexuality. Based on a hermeneutic phenomenological framework, seven in-depth, semi-structured interviews were conducted with five men and two women with moderate to severe cerebral palsy from Canada and Australia. Interviews were analyzed using Nvivo 9. Overall, the results and proposed model indicate that while interactional, public and private sexual scripts feature in all participants’ descriptions of their sexuality, interactional sexual scripts dominated participant’s definition of their sexuality. Rehabilitation counselling frameworks should be cognizant of the primary importance of interactional sexual experiences within their clients’ lives.

The relatively recent inclusion of sexuality in rehabilitation is based on the theory that all people have a right to sexual education, intimacy and intimate relationships (Parker, 2007). According to the World Health Organization (2012) sexual rights include “the right of all persons, free of coercion, discrimination and violence,” to attain the highest possible “standard of sexual health, including access to sexual and reproductive health services”. Sexual rights further include the right to seek, receive, and pass on information about sexuality and the right to sexuality education. Foremost, sexual rights encompass “the right to have one’s bodily integrity respected and the right to choose—to choose whether or not to be sexually active, to choose one’s sexual partners, to choose to enter into consensual sexual relationships, and to decide whether or not, and when to have children” (Parker, 2007). In addition, research has shown that sexuality is a key component for psychosocial wellbeing (Grov, Parsons, & Bimbi, 2010; Niet et al., 2010; Street et al., 2010). According to the World Association for Sexual Health (2012) “sexual health is more than the absence of disease. Sexual pleasure and satisfaction are integral components of well-being and require universal recognition and promotion”. Considering these conventions sexuality would be well placed within rehabilitation counselling as it can address potential sexual issues and provide understanding and education about sexual choices, sexual health, sexual negotiation and acknowledges the need and/or desire for satisfying sexual relationships.

Sexual Script Theory and Disability

According to Simon and Gagnon (1986, 1987, 2003) human sexuality is constructed via public, interactional and private sexual scripts. Public sexual scripts describe who is an appropriate sexual partner (Simon & Gagnon, 1986). However, this often excludes individuals with disabilities and their experiences of sexuality (Guildin, 2000). If people with disabilities are excluded from public (i.e. popular culture) portrayals of sexuality they may subsequently be excluded from sexual opportunities and be perceived (by themselves and others) to be unviable sexual partners (Dune, 2012a; Overstreet, 2008). Exclusionary constructions of sexuality with disability have a detrimental impact on how people living with cerebral palsy experience their sexuality (see Rurangirwaa, Van Naarden Braun, Schendel & Yeargin-Allsopp, 2006; Wazakili, Mpofu & Devlieger, 2009; Xenakis & Goldberg, 2010). Lawlor et al. (2006), for instance, indicated in their qualitative research on families of children with cerebral palsy that “reported barriers to participation were the attitudes of individuals and the ingrained attitudes of institutions…The attitudes of strangers towards the child and family which altered the choice of activity for some families” (p. 225). Thus sexual participation and negotiation as mediated by public and interactional sexual scripts may discourage sexual behaviour with people with a disability. As such, people with disabilities as well as typical others may internalize sexual scripts which ignore the variance in the human condition and experience (Esmail, Darry, Walter, & Knupp, 2010; Rembis, 2009). Without an appropriate model for sexuality with disability to inform rehabilitation counselling people with impairment may be relegated to expressing their sexuality within the confines of typical and performance-based frameworks.

Questioning Models of Sexuality with Disability

It is widely acknowledged within the field of rehabilitation that human sexuality is integral to clients’ quality of life and overall wellbeing (Brashear, 1978; Esmail, Darry, Walter, & Knupp, 2010; Rembis, 2009; Wiwanitkit, 2008). While incorporating aspects of sexuality into rehabilitation counselling is imperative to overall quality of life and wellbeing, the model, or lack thereof, upon which this is enacted, may be inherently exclusionary. Considering that sexuality is a relatively recent addition to the rehabilitation repertoire (Esmail, Darry, Walter, & Knupp, 2010; Rohleder & Swartz, 2012; Schulz, 2009) rehabilitation counselling, which strives towards an integrative/social model, has yet to comprehensively integrate this aspect of human experience within pedagogy or practice (Dune, 2012b). As such, rehabilitation counsellors may use the medical model of sexuality, popularised within typical populations, to address the “problem” of “limited” sexual performance and functioning in an effort to ‘help’ the client achieve near typical levels of sexual participation (see Mckee & Schover, 2001 on sexual rehabilitation after cancer).

This framework coincides with the type of hegemonic performance-based construction of sexuality perpetuated within public sexual scripts (i.e., popular culture, movies, television and magazines, see Guildin, 2000; Overstreet, 2008).

A medical and performance-based approach to sexuality with disability ignores the possibility that people with chronic disability (such as cerebral palsy) may construct, adapt and ascribe importance to sexual scripts differently than their typical peers (see also Rembis, 2009). This may be the case particularly considering that people with chronic disability are not often represented as sexual partners or sexual beings within sexual scripts in media. Without this recognition or representation rehabilitation counsellors may provide sexual advice, if at all, with models of typical sexual functioning and negotiation in mind. This is to say that while rehabilitation counselling may be well equipped to assist people in employment and community they may not be adequately equipped to address some of their clients’ major concerns about sexual participation and negotiation.

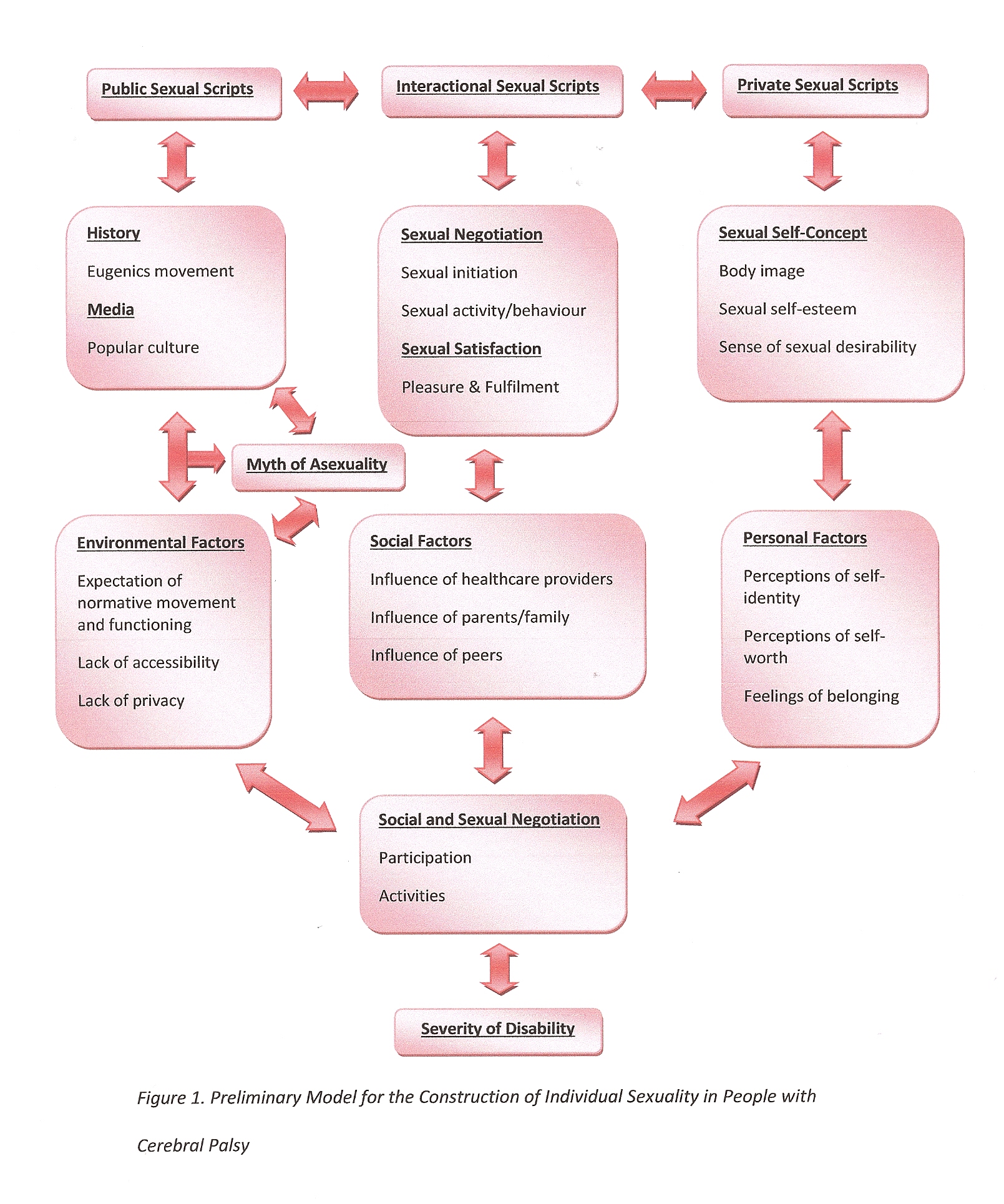

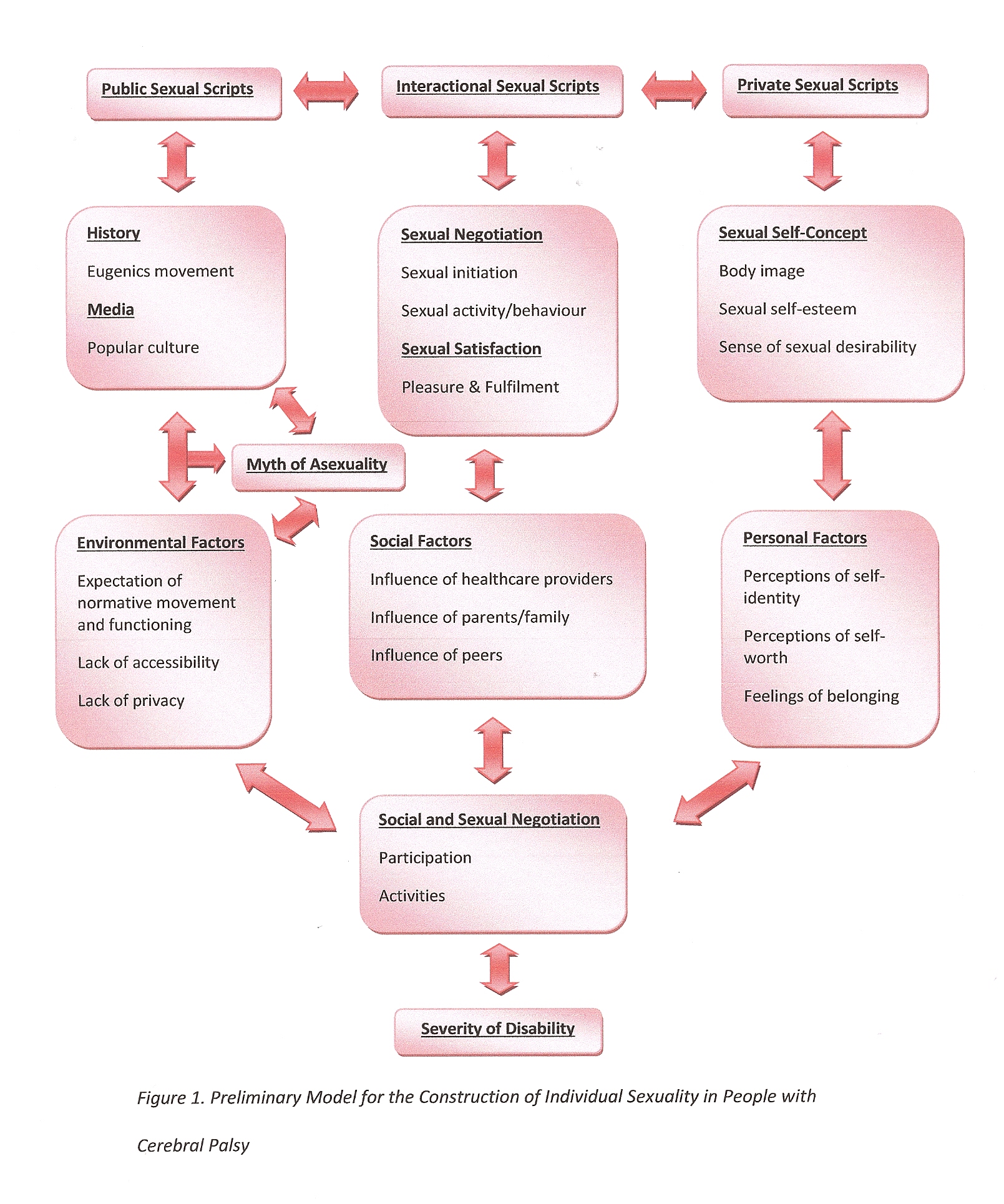

Sexuality and how people with cerebral palsy construct their sexuality is influenced by several explicit and implicit public, interactional and private factors. Therefore, a preliminary model that highlights these interactions was developed (see Figure 1). This model aimed to inform and support the hermeneutic phenomenological approach for the collection and analysis of data. Hermeneutic phenomenology was used as it studies interpretive structures (in this research sexual scripts and sexual constructions) of experience, how people engage with and understand these experiences in relation to ourselves and others (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, 2008). With its foundations in philosophical studies, hermeneutic phenomenology is useful for examining how public, interactional and private meanings are deposited and mediated through myth (i.e., myth that everyone should express sexuality in the same ways), religion (i.e., constructions of heterosexuality), art (i.e., erotica), and language (i.e., popular culture and interactional discourse). Ultimately, hermeneutic phenomenology aims to answer questions about the meaning of being, the self and self-identity (van Manen, 2002). This paper subsequently presents the modification of the following model based on the evidence gathered through this methodological lens.

Figure 1 illustrates how public, interactional and private scripts were proposed to influence the creation of individual sexuality. The preliminary model also includes specific elements of public, interactional and private scripts which influence constructions of sexuality and sexual identity in people with cerebral palsy. This model illustrates that sexual scripts are not directionally influential but are interdependent and constantly informed by factors like history, media, interactive sexual scripts and sexual self-concept(s). While this may be the case for all populations, the study was particularly interested in the influence and experiences of disability on individual constructions of sexuality.

This model proposes that factors such as the severity of one’s disability (through experiences of exclusion), the expectation to experience life like typical others and interactions with parents, family and peers, have an interdependent effect on how public, interactional and private scripts influence constructions of sexual scripts and sexuality in people with cerebral palsy. Although public and interpersonal scripts influence constructions of sexuality, individual factors imply heterogeneity between people with cerebral palsy and their resultant levels of social and/or sexual participation and preferred social and/or sexual activities (social and/or sexual negotiations).

This paper presents an excerpt of results from a doctoral project which used a hermeneutic phenomenological approach to explore the salience of sexual scripts (public, interactional and private) in constructions of sexuality by people with cerebral palsy towards the development of a revised model of sexuality with disability. In-depth interviews were conducted via email, telephone and/or face-to-face (based on participant preference). Face-to-face and telephone interviews had a duration of one to two and a half hours. A semi-structured interview guide was used for data collection and comprised of the following sections: demographics and severity of disability, private sexual scripts, interactional sexual scripts, public sexual scripts and reflective summary.

In order to gain information about the influence of private sexual scripts on constructions of sexuality for people with cerebral palsy, this section was aimed at allowing participants to express private sexual feelings, thoughts and fantasies. The questions in this portion of the main study interview guide aimed to allow participants to express any private sexual schemas which act as a significant factor in personal mental processes and inner dialogues. Question asked examined early sexual thoughts (i.e. “Can you please describe your early sexual thoughts or feelings to me?”), how participants would describe themselves and what they thought made them sexual and/or desirable (i.e. “What do you find sexy about yourself?”). These questions precluded the interactional section of the interview as they provided information about individual internalizations of sexuality.

In the interactional sexual scripts section of the interview participants were asked questions to ascertain if any interactional constructions of sexuality influenced the way in which they expressed and negotiated their sexuality. Questions about sexual relations were included in order to identify how people with cerebral palsy describe and measure mutually satisfying sexual activity. For example, “Please explain your romantic and/or sexual history” and “What would you consider the most important sexual transitions in your life?” were intended to allow participants to express their experiences with sexuality. The question “Can you describe to me the best sexual experience(s) you have had?” and “In your opinion, what makes ‘good’ sex good” were used to ascertain how participants conceptualized sexual experiences. Through the data collected the researcher aimed to identify instances in which interactional sexual schemas affected how participants experienced and conceptualized their sexual relationships, intimacy and sexual desires.

The questions in the public sexual scripts section of the interview aimed to gather information about the affect public sexual scripts had on constructions of sexuality as experienced by people with cerebral palsy. To understand how people with cerebral palsy were taught to construct (their) sexuality they were asked; “Where did you learn about sex? What did you learn about sex?” Further, participants were asked to reflect on their perception of romance (“What is your idea of romance?”) and satisfying sexual experiences (“What factors have influenced how you experience your sexuality?”). These questions were used to ascertain whether people with cerebral palsy described their sexuality as inclusive of popular constructions of sexuality as well as gain information about the participant’s perception of what their ideal sexual partner would be like and/or look like.

The data were analyzed for content by identifying topics and substantive categories within participants’ accounts in relation to the study's objectives. In addition, NVivo 9 was used to ascertain topical responses and emergent substantive categories, coding particularly for word repetition, direct and emotional statements and discourse markers including intensifiers, connectives and evaluative clauses.

This study included seven participants: five men and two women. Four of the participants were from Australia and three from Canada (see Table 1 for some demographic information). The study recruited from Canada and Australia in order to enhance the possibility of finding members of the target population to participate.

In Australia, participants were recruited through advertisements published in community newspapers and bulletins, through an advocacy group and in sexuality and/or disability focused newsletters and webpages. In addition, the snowballing technique was carried out at the end of participant interviews whereby each participant was asked if they knew someone who met the eligibility criteria and, if so, whether s/he would be willing to give that person a copy of the participant information sheet. The author did not know the identity of this person, and the interviewee who had referred someone were never told if that person agreed to participate in the project or not.

In Canada, participants were sought through the Attendant Care Program in Ottawa, Ontario, Canada. The Attendant Care Program services two of the major educational institutions in the city with round-the-clock provision of personal care for tertiary students with disabilities who live in the university residence buildings. The program, which has been running for over 20 years, services approximately 50 – 60 students per year with numbers increasing every year. Due to the client-directed style of the program clients are provided with the resources they need to live independently through the provision of dignity-focused care and accessible living arrangements. As the author was formerly employed by the service she forwarded the coordinator of the program the details of this project and was informally given permission to ask clients (the majority of whom had cerebral palsy) of the Attendant Care Program if they would like to participate.

Table 1. Participant Summary

Participant (Pseudonym) |

Sex |

Type of Cerebral Palsy |

Assistive Devices or Services |

Socio-economic Status, education and ethnicity |

Medical Interventions |

Living Arrangements |

Sexual Profile |

John |

Male |

Spastic Quadriplegic Cerebral Palsy (severe) |

Mechanized wheelchair, daily personal assistance from others |

Upper-middle class, tertiary education, Caucasian Australian |

Major musculoskeletal surgery during childhood and adolescence. Rehabilitative maintenance. |

Lived with his mother in his family’s home |

Heterosexual, sexually active, no history of long term sexually intimate relationships |

Mary |

Female |

Spastic Paraplegic Cerebral Palsy (moderate) |

Occasional use of crutches |

Middle class, tertiary education, Caucasian Australian |

Major musculoskeletal surgery during childhood and adolescence. Rehabilitative maintenance. |

Lived independently in an apartment with her partner |

Heterosexual, in a long term sexual relationship at time of interview |

Brian |

Male |

Ataxic Quadriplegic Cerebral Palsy (severe) |

Mechanized wheelchair, daily personal assistance from others |

Middle class, tertiary education, Caucasian Australian |

Major musculoskeletal surgery during childhood and adolescence. Rehabilitative maintenance. |

Lived in an independent living facility |

Heterosexual, sexually active, no history of long term sexually intimate relationships |

|

Leah |

Female |

Spastic Paraplegic Cerebral Palsy (moderate) |

Mechanized wheelchair, daily personal assistance from others |

Lower-middle class, tertiary education, Caucasian Australian |

Major musculoskeletal surgery during childhood and adolescence. Rehabilitative maintenance. |

Lived in an apartment with her boyfriend. |

Heterosexual, in a long term sexual relationship at time of interview |

Ian |

Male |

Ataxic Quadriplegic Cerebral Palsy (severe) |

Mechanized wheelchair, daily personal assistance from others |

Lower-middle class, tertiary education, Caucasian Canadian |

Major musculoskeletal surgery during childhood and adolescence. Rehabilitative maintenance. |

Lived in an independent living facility. |

Heterosexual, sexually active, no history of long term sexually intimate relationships |

Trevor |

Male |

Spastic Quadriplegic Cerebral Palsy (severe) |

Mechanized wheelchair, daily personal assistance from others |

Upper-middle class, tertiary education, Caucasian Canadian |

Major musculoskeletal surgery during childhood and adolescence. Rehabilitative maintenance. |

Lived in an independent living facility |

Heterosexual, in a long term sexually intimate relationship at time of the interview |

Alex |

Male |

Spastic Quadriplegic Cerebral Palsy (severe) |

Mechanized wheelchair, daily personal assistance from others |

Upper-middle class, tertiary education, Caucasian Canadian |

Major musculoskeletal surgery during childhood and adolescence. Rehabilitative maintenance. |

Lived in an independent living facility |

Homosexual, high frequency of casual sexual encounters, no history of long term sexually intimate relationships |

Participant data suggests that interactional sexual scripts are of primary importance to how people with cerebral palsy construct their sexuality. Public and private sexual scripts were of secondary and tertiary (respectively) importance to the construction of sexuality by people with cerebral palsy (see Table 2 for a breakdown of the major themes, subthemes and nomination frequency).

Table 2. Relative Salience of Public, Interactional and Private Sexual Schema Major Themes and Sub-themes

Sexual Script |

Major Theme |

Major Theme Ranking |

Sub-Themes |

Frequency of Nomination |

Sub-theme Ranking |

Interactional |

Perception of Sexual Experiences with Others |

1 |

|

23 |

1 |

Public |

Contemporary Media and Popular Culture |

2 |

|

7 |

6 |

The Myth of Disability and Asexuality |

5 |

|

7 |

14 |

|

Expectations of Normative Movement and Functioning |

6 |

|

5 |

16 |

|

Issues of Accessibility |

7 |

|

5 |

19 |

|

Private |

The Intersection between Disability and Sexual Identity |

3 |

|

7 |

9 |

Perceptions of Sexual Desirability |

4 |

|

7 |

12 |

|

Body Esteem |

8 |

|

3 |

22 |

|

Sexual Agency |

9 |

|

3 |

25 |

|

Sexual Esteem |

10 |

|

3 |

28 |

Modified Conceptual Model

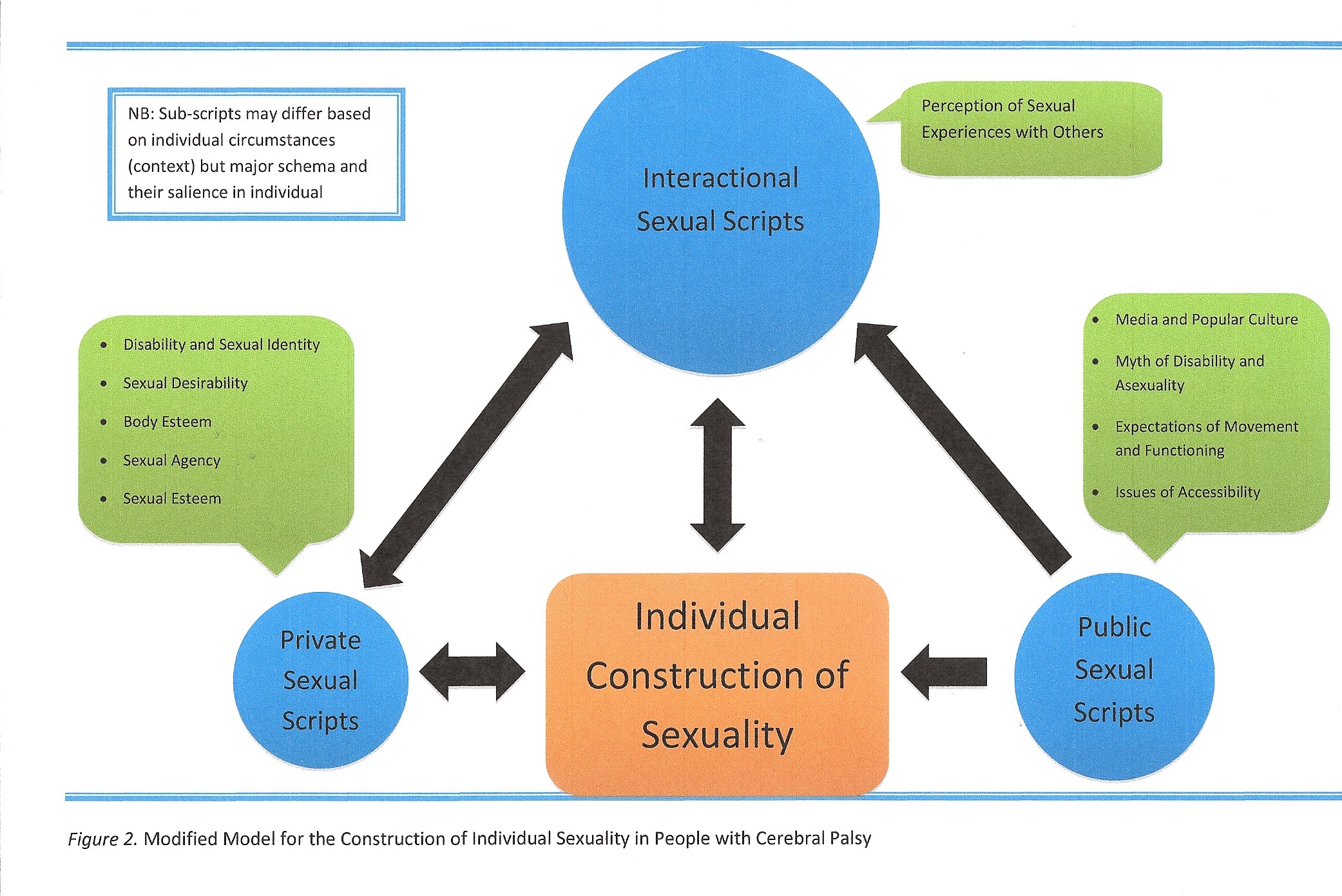

On the basis of these findings, a modified model to illustrate sexual constructions with disability is proposed (see Figure 2). The preliminary model (Figure 1) illustrated public, interactional and private scripts and sub-scripts equally. The modified conceptual model indicates that interactional scripts are primary to public and private scripts. Specific elements of interactional, public, and private sexual scripts which influence constructions of sexuality in people with cerebral palsy emerged from the thematic analysis. While both the preliminary model and modified conceptual model illustrated that sexual scripts are not directionally influential – but are relatively interdependent – the modified conceptual model shows that individual constructions of sexuality with cerebral palsy have a bidirectional relationship with both interactional and private sexual scripts. This is to say that how people experience their sexuality with others and how they privately conceptualize their sexuality are interdependent processes. However, public sexual scripts have a unidirectional influence on interactional sexual schema and individual constructions of sexuality with cerebral palsy. As such, contemporary media and popular culture, for example, influence how people with cerebral palsy participate in sexual relationships but not the other way around. Public sexual schema influence how people with cerebral palsy interact with others and how they consolidate their sexuality.

This model proposes that participation in sexual activities with others is of more salience to constructions of sexuality than, for example, severity of one’s disability, expectations to experience life like typical others, sexual self-concept(s) or media and popular culture. Although interactional scripts influence constructions of sexuality, individual factors imply heterogeneity between people with cerebral palsy and their resultant levels of social and/or sexual participation and preferred social and/or sexual activities (social and/or sexual negotiations).

The influence of interactional, public and private sexual schema may have varying degrees of salience depending on context. Several circumstantial elements may influence individual constructions of sexuality with cerebral palsy. For instance, medical interventions and severity of impairment, living arrangements, modes of communication, intersecting experiences of oppression, gender, ethnicity, culture and socio-economic status and relationship history may have more influence on certain schema or sub-schema than others. While individual contexts and circumstances may alter the construction of one’s sexuality it is noted that it may only influence sexual sub-schema and not have a significant effect on the salience of interactional, public or private sexual schema. This is to say, for example, that an individual with severe cerebral palsy may be influenced more by issues of accessibility than another with moderate cerebral palsy. However, based on the modified conceptual model, sexuality for both individuals will primarily be influenced by the type and quality of sexual experiences they have with others.

As such, sexual interactions with others seem to influence the sexual experiences regardless of circumstance or disability status (see also Hassouneh-Phillips & McNeff, 2005; Hoefinger, 2010; Mitchell, 2010). It would seem this conceptual model would explain sexual participation with cerebral palsy in many contexts. While the sub-scripts may change, the relative salience of interactional, public and private scripts remains the same (see also Anderson & Cyranowski, 1994; Anderson, Cyranowski & Espindle, 1999; Bancroft, 1997).

Based on their developmental history, people with cerebral palsy may be in consistent contact with rehabilitation workers throughout their lives (Dune, 2012b). The relationships built during these encounters can be the foundation for both parties to encourage positive constructions of sexuality with disability which empower and acknowledge individual agency. The findings of the present study as well as the proposed conceptual model suggest that rehabilitation counsellors and people with cerebral palsy should not assume that living with significant disability is the primary basis of opportunities for social and sexual participation. In addition, rehabilitation workers and people with cerebral palsy need to acknowledge that sexuality as constructed and experienced by someone with significant disability is not deficient and/or an alternative to the “norm” (see Rembis, 2009 on the social model of disabled sexuality and Schulz, 2009 on rehabilitation as normalization).

In this regard, rehabilitation counsellors should depart from the medical/performance-based model of sexuality and efforts to restore or promote typical sexual behaviour. Instead the client’s constructions and experiences should be centralized such that rehabilitation facilitates the sexuality they do and want to experience. In this respect, the results indicate that people with cerebral palsy are knowledgeable and educated about their own sexuality and experience of disability. Research that explores rehabilitation workers’ attitudes and constructions of sexuality with disability is needed in order to ascertain levels of comfort, skill and importance they attribute to facilitating sexual participation and negotiation of their clients. Such research would contribute towards the development of client and rehabilitation counsellor as equal contributors of knowledge and understanding towards the formulation of sexual health and wellbeing.

This study had some limitations; 1) cultural homogeneity, 2) restrictions of qualitative methodology, and 3) constraints of script theory. First, the cultural frame was homogenous. Namely all the participants in this study were Caucasian, from developed nations, had completed post-secondary education and were within the spectrum of middle class socio-economic status. As such, the participants of this study may only represent a range and depth of socio-sexual development experienced by members of privileged ethnic groups and resourced nations. Limited cultural and linguistic diversity (CALD) (Rao, Warburton & Bartlett, 2006) may have skewed the findings. For instance, CALD within the present study may have made intersecting experiences of oppression more salient or it may have been identified as a sub-schema under public or interactional sexual schema. Hence, without information from CALD respondents, the findings may lack cross-cultural utility. In addition, socioeconomic status may have a significant effect on socio-sexual agency and independence for people with cerebral palsy. For instance, people with significant disabilities with financial means may have more flexibility or autonomy in the provision of their health care than those who do not (Schillmeier, 2007). Financial means may also support independent living, social opportunities and sexual development. Research which includes a more culturally, ethnically and financially diverse sample is needed in order to determine whether these points of diversify would have an impact on the findings of this study.

Second, the qualitative methodology used within this study allowed for rich descriptive and contextual information. Interpretive inquiry allows for some data contours to be emphasized more than others (Mayoux, 2006). For instance, the data collected is mediated by the investigator’s ability to ask questions or probe answers which allowed respondent’s to comprehensively articulate their concepts, conceptualizations and conceptions of sexuality with disability. In doing so respondents may have found it easier to express some or certain sexual schema and not others due to their abstract nature or convolutions within the questions. While the in-depth interview technique used within the study provided insight into the meanings people with cerebral palsy give to their sexual lives a more ethnographic approach may have been beneficial. For example, if the investigator had spent more time with the participants in a non-interview environment they may have gained addition access to contextual information which may have been useful in the interpretation of participant data (Shuttleworth, 2000). This addition of contextual information may have alleviated the issue of convoluted questions or abstract articulations of sexual phenomena. Research which explores constructions of sexuality with cerebral palsy using different qualitative techniques (i.e., focus groups, case studies and observations) would further clarify the findings of this study.

Finally, sexual script theory was the theoretical basis for this research. Sexual script theory however, delineates sexual influences into public, interactional and private sexual schema. The results from the present inquiry indicate that public, interactional and private sexual schema are interdependent in their effect on constructions of sexuality with cerebral palsy. Interdependence of theoretical constructs introduces interdeterminancy (Dworkin, 1985). This is to say that sexuality as constructed by people with cerebral palsy cannot be dissected and explained within the confines of public, interactional or private sexual schema. The findings of this study emphasize that people with cerebral palsy are agents in the construction of their sexuality. Bandura’s social cognitive theory (1986, 1997, 2006), which highlights people as social agents, may therefore be a better theory to apply to constructions of sexuality with cerebral palsy. Research which employs Bandura’s social cognitive theory and constructions of sexual with disability would be beneficial to further understanding agency and sexuality with disability.

This paper sought to present how people with moderate to severe disability construct their sexuality in order to develop a conceptual model of sexuality with disability relevant to rehabilitation counselling. This study found that constructions of sexuality with cerebral palsy are primarily influenced by interactional sexual schema. As such, the proposed conceptual model highlights sexual participation and negotiation as key elements of sexual wellbeing with cerebral palsy. While the sub-scripts may change, the relative salience of interactional, public and private scripts remains the same. The results and the model presented bring to the fore discussions the importance of acknowledging sexual agency within people with chronic disabilities, like cerebral palsy. In regards to sexuality with disability rehabilitation counselling should centralize, facilitate and promote client constructions and experiences which may or may not reflect typical representations of sexual functioning or interactions.

Anderson, B. L., & Cyranowski, J. M. (1994). Women's Sexual Self-Schema. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology , 67 (6), 1079-1100.

Anderson, B. L., Cyranowski, J. M., & Espindle, D. (1999). Men's sexual schema. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology , 76 (4), 645-661.

Bancroft, J. (1997). Researching sexual behavior: Methodological issues. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall.

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York: 1997.

Bandura, A. (2006). Guide for constructing self-efficacy scales. In F. Pajares, & T. C. Urdan, Self-efficacy beliefs of adolescents (pp. 307-338). Charlotte: Information Age Publishing.

Beauchamp, T. L., & Childress, J. F. (2009). Principles of biomedical ethics. 6th ed. New York: Oxford University Press.

Brashear, D. B. (1978). Integrating human sexuality into rehabilitation practice. Sexuality and Disability, 1(3), 190-199.

Brufee, K. (1993). Collaborative learning. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Dune, T. M. (2012a). Understanding Experiences of Sexuality with Cerebral Palsy through Sexual Script Theory. International Journal of Social Science Studies, 1(1), p1-12.

Dune, T. M. (2012b). Sexuality and Physical Disability: Exploring the Barriers and Solutions in Healthcare. Sexuality and Disability, 30, 247-255.

Dworkin, R. A. (1985). "Why Should Liberals Care about Equality" in A Matter of Principle. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Entwistle, V. A., Carter, S. M., Cribb, A., & McCaffery, K. (2010). Supporting Patient Autonomy: The Importance of Clinician-patient Relationships. J Gen Intern Med , 25 (7), 741-745.

Esmail, S., Darry, K., Walter, A., & Knupp, H. (2010). Attitudes and perceptions towards disability and sexuality. Disability & Rehabilitation, 32(14), 1148-1155.

Grov, C., Parsons, J. T., & Bimbi, D. S. (2010). The Association between Penis Size and Sexual Health Among Men Who Have Sex with Men. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 39(3), 788-797.

Guildin, A. (2000). Self-claiming sexuality: Mobility impaired people and American culture. Sexuality and Disability, 18 (4), 233-238.

Hassouneh-Phillips, D., & McNeff, E. (2005). “I Thought I was Less Worthy”: Low Sexual and Body Esteem and Increased Vulnerability to Intimate Partner Abuse in Women with Physical Disabilities. Sexuality and Disability, 23 (4), 227-240.

Hoefinger, H. (2010). Negotiating Intimacy: Transactional Sex and Relationships Among Cambodian Professional Girlfriends. London: Goldsmiths College, University of London.

Lawlor, K., Mihaylov, S., Welsh, B., Jarvis, S., & Colver, A. (2006). A qualitative study of the physical, social and attitudinal environments influencing the participation of children with cerebral palsy in northeast England. Developmental Neurorehabilitation, 9 (3), 219-228.

Mayoux, L. (2006). Quantitative, qualitative or participatory? which method, for what and when. In V.

Desai, & R. B. Potter, Doing development research (pp. 113-129). London: Sage.

McKee, A. L., & Schover, L. R. (2001). Sexuality rehabilitation. Cancer, 92(S4), 1008-1012.

Mitchell, J. W. (2010). Examining the role of relationship characteristics and dynamics on sexual risk behavior among gay male couples. Portland: Oregan State University.

Niet, J. E., de Koning, C. M., Pastoor, H., Duivenvoorden, H. J., Valkenburg, O., Ramakers, M. J., et al. (2010). Psychological well-being and sexarche in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Human Reproduction, 56(6), 1497-1503.

Overstreet, L. C. (2008). Splitting sexuality and disability: A content analysis and case study of internet pornography featuring a female wheelchair user. Sociology Theses. Paper 22.

Parker, R. G. (2007). Sexuality, Health, and Human Rights. American Journal of Public Health, 97(6), 972 - 973.

Rao, D. V., Warburton, J., & Bartlett, H. (2006). Health and social needs of older Australians from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds: issues and implications. Australasian Journal on Ageing , 25 (4), 174-179.

Rembis, M. A. (2010). Beyond the binary: rethinking the social model of disabled sexuality. Sexuality and Disability, 28(1), 51-60.

Rohleder, P., & Swartz, L. (2012). Disability, sexuality and sexual health. Understanding Global Sexualities: New Frontiers, 138.

Rurangirwaa, J., Van Naarden Braun, K., Schendel, D., & Yeargin-Allsopp, M. (2006). Healthy behaviours and lifestyles in young adults with a history of developmental disabilities. Research in Developmental Disabilities , 27 (4), 381-399.

Saltiel, I. M. (1998). Defining Collaborative Partnerships. New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education , 79, 5-11.

Schillmeier, M. (2007). Dis/abling spaces of calculation: blindness and money in everyday life. Environment and Planning D. , 25, 594-609.

Schulz, S. L. (2009). Psychological theories of disability and sexuality: A literature review. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 19(1), 58-69.

Shuttleworth, R. P. (2000). The Search for Sexual Intimacy for Men with Cerebral Palsy. Sexuality and Disability , 18 (4), 263-282.

Simon, W., & Gagnon, J. H. (1986). Sexual scripts: Permanence and change. Archives of Sexual Behaviours, 15 (2), 97-120.

Simon, W., & Gagnon, J. H. (1987). A sexual scripts approach. In J. H. Geer, & W. T. O'Donohue, Theories of human sexuality (pp. 363-383). London: Plenum Press.

Simon, W., & Gagnon, J. H. (2003). Sexual scripts: Origins, influences and changes. Qualitative Sociology, 26 (4), 491-497.

Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. (2008). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Stanford: Stanford University: The Metaphysics Research Lab.

Street, A. F., Couper, J. W., Love, A. W., Blaoch, S., Kissane, D. W., & Street, B. G. (2010). Psychosocial adaptation in female partners of men with prostate cancer. European Journal of Cancer Care, 19(2), 234-242.

van Manen, M. (2002). Writing in the dark: Phenomenological studies in interpretive inquiry. London: Althouse.

Wazakili, M., Mpofu, R., & Devlieger, P. (2009). Should issues of sexuality and HIV and AIDS be a rehabilitation concern? The voices of young South Africans with physical disabilities. Disability and Rehabilitation, 31 (1), 32-41.

Wiwanitkit, V. (2008). Sexuality and rehabilitation for individuals with cerebral palsy. Sexuality and Disability, 26(3), 175-177.

World Health Organization. Gender and reproductive health: working definitions. Available at: http://www.who.int/reproductive-health/gender/sexual_health.html. Accessed December 19, 2012

Xenakis, N., & Goldberg, J. (2010). The Young Women's Program: A health and wellness model to empower adolescents with physical disabilities. Disability and Health Journal, 3 (2), 125-129.